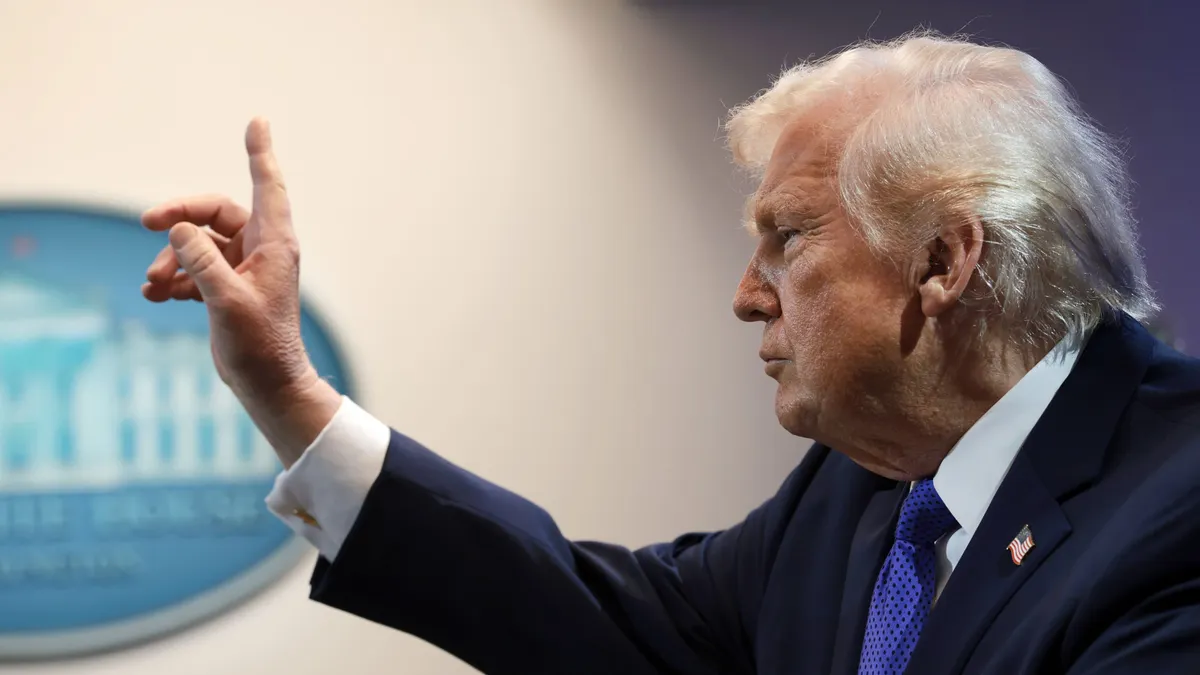

The Trump Admin.’s Environmental Protection Agency has set its sights on encouraging automakers to eliminate stop-start systems that were widely adopted starting 15 years ago to help meet Corporate Average Fuel Economy regulations.

EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin says stop-start is a system every driver "hates." Zeldin announced earlier this month an effort to eliminate incentives for stop-start technology, stating that the feature offers minimal carbon-emissions benefits, is widely disliked by consumers and prematurely wears out starter systems.

Zeldin’s comments have ignited a discussion as to whether the systems – an industry segment worth $67 billion a year, according to global consulting firm IMARC Group, are delivering on planned carbon savings.

Initially introduced as a fuel-saving measure, these systems became widely adopted following regulatory pressure to reduce carbon-dioxide emissions in the U.S. during the Obama Admin. and in the EU at the same time, and to improve fuel economy in both light-duty passenger and commercial vehicles.

The biggest suppliers of stop-start systems are Bosch, Valeo, Denso, Hitachi and SEG Automotive.

Over the past two decades, stop-start systems have transitioned from a premium feature to a near-ubiquitous standard in internal-combustion-engine (ICE) vehicles across much of the developed world.

The technology was included in 65% of U.S. vehicles in 2023, a jump from 45% in 2021, 9% in 2016 and 1% in 2012, according to Battery Council International. According to EPA estimates from more than decade ago, the feature can improve a vehicle's fuel economy by between 4% and 5%. It also eliminated nearly 10 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year as of 2023, the council states.

The EPA does not require stop-start technology, but automakers that adopt it are given extra fuel-economy credits. The EPA says it could “ban” the systems, but it’s more likely that the agency would just cancel credits that automakers could claim for equipping vehicles with such a system.

While automakers have widely adopted these systems to help meet CAFE standards, some have expressed reservations over the years regarding the real-world positive impact of stop-start systems and the wear on engine components. In 2010, for example, when Ford announced plans to introduce stop-start systems in North America, initially with 4-cyl. engines and later expanding to V-6s and V-8s, the automaker acknowledged the need for more-robust batteries to handle the increased demands of stop-start systems.

“Do stop-start systems reduce carbon emissions? It’s debatable,” says Cooper Ericksen, senior vice president of product, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and mobility planning and strategy. Toyota recently met with Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy, and the cabinet secretary expressed his disdain for the technology as he has experienced it on his pickup truck.

Some studies and reports have shown that start-stop systems can offer fuel savings, but these benefits may be more pronounced in city driving than on highways. AAA tests have indicated the technology can improve fuel economy by 5%-7%.

Not all stop-start systems are created equal. Some perform better than others. Consumer Reports, for example, has highlighted both positive and negative aspects of stop-start systems. For example, in their evaluation of the 2025 Chevrolet Equinox, the product-testing outlet praised the vehicle's stop-start system for its “smooth and quick re-engagement of the engine,” but acknowledged that, taking into account all the vehicles they test, the system's operation in some models can be less than seamless.

The Case for Stop-Start

The core idea behind stop-start is straightforward: idling consumes fuel and emits CO₂ without moving the vehicle. Studies by the U.S. Department of Energy and Argonne National Laboratory in the early 2000s determined that a typical gasoline vehicle burns about 0.2 to 0.5 gallons of fuel per hour while idling. Stop-start systems were developed to eliminate this waste in dense urban driving.

Not surprisingly, the technology was piloted in Europe. Volkswagen introduced the first production car with a start-stop system in a European model in 1983. While early forms of the technology existed in the 1970s, it wasn't until the 1980s that it was widely adopted in Europe.

According to Society of Automotive Engineers research, such systems can improve fuel economy by 3% to 10% in city driving depending on traffic patterns, engine size and system integration. These savings can be significant in congested urban environments where vehicles may idle for extended periods.

In controlled lab tests conforming to urban driving cycles like the New European Driving Cycle and later the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), stop-start technology reliably demonstrated reductions of 2 to 5 grams of CO₂ per kilometer.

Countries with Regulatory Encouragement

While very few governments explicitly "mandate" stop-start systems by name, regulatory pressure through CO₂ emissions targets and fuel-economy standards has indirectly made stop-start systems a necessity for compliance. Here is a summary of leading regions:

- European Union: The EU’s fleet average CO₂ target of 95 g/km (phased in from 2020) made stop-start systems virtually essential. Nearly all ICE and mild-hybrid vehicles sold in the EU now have this technology, according to the European Environment Agency.

- Japan: Under the Top Runner Program and strict fuel-economy standards, Japanese automakers adopted stop-start systems aggressively as early as 2008. Over 90% of new cars sold in Japan by 2020 were so equipped, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation.

- China: China’s Stage V and VI emission standards (similar to Euro 5 and 6) encouraged adoption. Stop-start is widely deployed in urban-focused vehicles and compact sedans, according to Energy Foundation China.

- U.S.: While not mandated federally, Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards and greenhouse-gas regulations under the EPA and NHTSA strongly incentivized stop-start adoption, especially from the 2017 model year onward. Many automakers use it to meet CAFE targets without full hybridization.

Carbon and Fuel Savings

Quantifying total global carbon savings from stop-start systems is complex, but some estimates have been done.

- Europe: According to a 2022 report from the European Commission and ACEA (European Automobile Manufacturers’ Assn.), stop-start systems contributed to roughly 3%–4% of total fleet CO₂ reduction between 2015 and 2020. For a fleet of about 250 million vehicles, that translated into 15 to 20 million metric tons of CO₂ avoided annually.

- U.S.: The EPA’s 2020 compliance report noted that stop-start systems contributed about 2.4 g/mi of average CO₂ savings in ICE vehicles compared to equivalent models without the technology. Based on fleet sizes and average miles driven, this equated to roughly 2 million–3 million metric tons of CO₂ avoided annually by 2020.

- Global Estimate: Industry analysts at IHS Markit estimated that by 2023, stop-start systems globally had avoided more than 50 million metric tons of CO₂ emissions cumulatively.

Still, some studies have raised doubts about the real-world effectiveness and side effects of stop-start systems: A 2017 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation found that real-world CO₂ benefits were often 30%–50% lower than regulatory test results due to less frequent stop-start activation in actual traffic, driver overrides and system temperature limitations.

Some drivers perceive stop-start as intrusive, particularly in extreme temperatures or with early implementations that caused delays or jolts on restart. This has led to high rates of system deactivation by users on vehicles that provide the shut-off feature, undermining intended savings.

Without regulatory incentives, automakers are likely to phase out start-stop systems to reduce costs. With billions being spent now on tariffs, every cost saving is getting fresh looks.