Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

Related document: 2010 Ward's MegaDealer 100 List

Many auto executives watched in horror as the megadealer movement went public in the 1990s.

They thought if publicly traded dealership chains got big enough, the growing megadealers would start dictating terms to them, rather than what typically had been the other way around.

Some active imaginations even conjured up the possibility of a dealership chain getting so big and powerful, it would even brand its own car line.

That didn't happen. Nor did megalomaniacal megadealers try to seize control of the auto industry. But they have become a force that sometimes butts heads with auto makers.

For example, many megadealers, notably AutoNation Inc., sensing an economic storm coming a few years ago, adamantly refused to take on excess inventory for its hundreds of stores, despite auto makers' efforts to push overproduction problems onto dealers.

In the past, the drill routinely went like this: Auto makers built too many cars because of their fixed costs. They then shoved the excess output on individual dealers who griped about it but took the vehicles, not wishing to risk factory reprisals.

But megadealers spoke out and stood firm against the production-push business model.

“No one has screamed more against that than me,” says AutoNation CEO Michael Jackson. “Basically, labor was a fixed cost, so manufacturers produced cars people didn't want and stuffed the channel like a Thanksgiving turkey.”

It hurt profits, prices and residual values. “It dominated the industry and had a bad, ugly ending, but production push is dead,” Jackson declares.

If not officially dead, then it is certainly finished as a standard operating procedure. Megadealers can take some of the credit for that. So can a major recession, plunging auto sales and post-bankruptcy reorganization plans for General Motors Co. and Chrysler Group LLC.

Megadealers — and many other dealers who follow similar business practices — also can credit themselves for coming out of the recession without critical injuries. They did so by reacting quickly to the dramatic drop in vehicle sales, from 16.1 million in 2007 to 10.4 million in 2009.

“Car dealers have variable-expense structures, meaning they can cut expenses on a dime,” says Sheldon Sandler, CEO of Bel Air Partners, a firm that facilitates the buying and selling of dealerships.

The Ward's Megadealer 100, like the rest of the auto industry, suffered through a painful 2008-2009. But with the economy now improving, many industry observers say megadealers are poised for success.

There are a few reasons for that. One, their economies of scale. Two, they tend to be better capitalized than individual dealerships. Three, they are disciplined, professionally run organizations.

“We have experience you can't buy,” says Sid DeBoer, chairman of Lithia Motors Inc. “Last year showed the auto industry can survive anything.”

Lithia reduced its work force from 6,000 to 4,000 during the recession. It sold some underperforming stores. It also shifted its mix of brand representation to 50% import, 50% domestic.

“We were once 40% Chrysler,” DeBoer says. “We made a big bet when Daimler (AG) bought Chrysler. We thought it would be the best auto company in the world.”

That didn't happen, but DeBoer has no hard feelings; he still drives a Chrysler.

With auto sales up 15% so far this year, a leaner 162-store Lithia is making money, even though auto sales aren't where they were a few short years ago. “Profits really show up when you've got your bases covered,” DeBoer says.

Responding to hard times, AutoNation made hard decisions, such as reducing its workforce by 15% and cutting costs by $400 million.

But it wasn't a slash-and-burn strategy The company sought to avoid creating a crippled remaining staff or one that might bolt.

“We wanted to make sure compensation was adequate for the remaining jobs,” AutoNation President Mike Maroone says. “When we get to the other side of the abyss, we don't want to see our best talent at a competitor across the street or out of the industry altogether.”

As times get better, AutoNation looks to add personnel, he says. “There will come a time when volume outstrips staffing levels.”

But virtually all megadealers vow that excess costs cut during austerity budgeting won't readily get put back in.

“The key is not to let costs creep back up as profits go up,” says Earl Hesterberg, CEO of Group 1 Automotive Inc. “This always has been a low-margin business.”

The economy still faces serious issues of high unemployment and low housing values, Maroone notes. “But we are bullish. Auto retailers are known for their optimism, even if a whole lot of it might not be out there.”

A major cause for hope is that the auto industry largely has stopped overproducing vehicles, he says. “Moving to a demand system will forever change the business.”

Not all megadealers laid off employees.

“We didn't let one person go,” says Tammy Darvish, a dealer principal at Darcars Automotive Group, a 26-store family-owned business founded by her father, John Darvish, and based in Silver Spring, MD.

“We are down by 200 people, but that is by pure attrition,” she says. “My father said, ‘No layoffs.’”

Tammy Darvish co-led a lobbying effort to get Congress to require arbitration for dealers who lost their franchises because of GM and Chrysler' reorganization plans.

“I made a choice to be part of something rather than be subjected to something,” she says of her role as a dealer activist.

Darcars lost some stores in the shakeout. She says it is unfair to ask dealers to invest millions of dollars in facilities, then yank franchises with no compensation.

In contrast to Darvish's efforts, AutoNation lost seven Chrysler and four GM stores but isn't fighting to get those back. “We're moving on,” Maroone says.

He understands why the two auto makers cut dealerships, but raps the method of the operation.

“When you have 3,500 Chrysler dealers with extremely low throughput, it's a problem,” Maroone says. “I didn't like the way they did it; it was done painfully. But no question, domestic auto makers were overdealered.”

Some megadealer executives know firsthand how auto companies operate. That's because they once worked for auto makers.

For instance, Hesterberg was an auto executive at Ford Motor Co. before becoming the head of Group 1 based in Houston.

Jackson has gone full circle. First he was a Mercedes-Benz dealer. Then he became president of Mercedes' North American operations, joining AutoNation in 1999.

Auto executives and dealers see things differently, he says. “If there is a room full of dealers and auto executives and you picked a non-automotive subject to talk about, I could tell you after a half hour who is a dealer and who is a manufacturer.”

Jackson says AutoNation began “managing very defensively” when it detected a few years ago that “a day of reckoning was coming.”

He foresees a measured, slow economic recovery. “There is no ‘on’ switch for that,” he says. “We kept a conservative balance sheet and a lean inventory. Now that we are past the worst, we are much more open to great opportunities.”

That includes once again shopping for new stores, an activity that had been put on hold. “We are looking for acquisition growth,” Maroone says.

Many recovering megadealers now are looking for good bets to make. “Last year was survival, now I'm looking for opportunities,” DeBoer says.

He retains faith in Chrysler. Many Chrysler-brand dealerships are available for bargain prices, he notes. “If it were just up to me, I'd buy them. But we're not a private company.”

DCH Auto Group based in South Amboy, NJ, is focusing on profits this year after a cost-cutting 2009, says its chairman, Shau-wai Lam.

It is scouting for new dealerships, but not in the U.S. “We are looking at opportunities in China,” says Lam, a native of that nation.

The 27-store DCH is known for acting quickly and decisively. When GM started showing early signs of losing faith in its Saturn brand, DCH began divesting itself of its six Saturn stores.

The dealership chain had sold those off by the time GM announced in October it was ending Saturn. That came after a failed, last-ditch effort to sell Saturn to the Penske Automotive Group, a megadealer that sought to take auto retailing to a level in which the distribution side would control the brand.

Lam modestly credits his management team for seeing the handwriting on the wall when it came to Saturn's fate. “We had originally put hope in the future of Saturn,” he says.

DCH President and CEO Susan Scarola says her operational goal is to become “much more efficient and take advantage of opportunities.” She adds: “It is key that we are awake and watching what is happening.”

Meanwhile, business slowly is improving for the 5-store Hitchcock Automotive Resources in City of Industry, CA, says Chairman Fritz Hitchcock.

“It's getting a bit better every day, every month,” he says. “Housing is still a big economic issue in California, so we are hanging on to our hats.”

His dealership group continues to cut costs. That includes reducing payroll and seeking better deals from vendors.

Productivity is up, despite the job cuts, Hitchcock says. “I think it's a matter of the people who are left are happy to have jobs. Plus, we retained top performers. Job security based on tenure or seniority is not an issue in automotive retailing.”

Although dealer-manufacturer relations are better now than at some low points in the past, some tensions remain. Many dealers, large and small, feel auto companies take advantage of them and don't share the wealth enough.

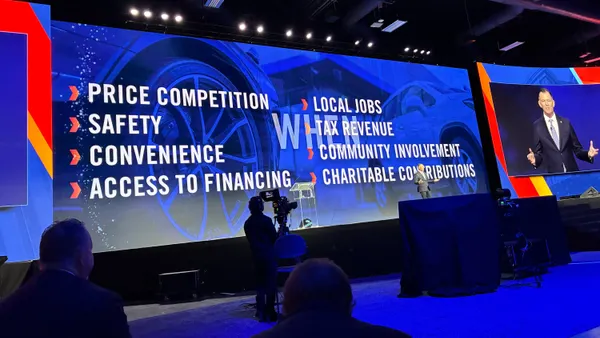

Auto makers should offer dealers better new-car profit margins, Ed Tonkin, chairman of the National Automobile Dealers Assn., says at an auto conference put on by NADA and IHS Global Insight.

He co-runs the Portland, OR-based Ron Tonkin Family of Dealerships, a member of the Ward's Megadealer 100.

“Returns must get better for those of us dealers who learned to survive,” Tonkin says. “Maybe I'm crazy, but manufacturers need to understand that for them to succeed they have to put back some margin for dealers.

“We can't survive on air.”

When people ask Jackson what he does for a living, “I could say I'm a vehicle-sales tax collector, because the state makes more money on a sale than I do.”

Being a former auto executive gives Hesterberg special insight into manufacturer-dealer relations.

“The factory is not irrational, it's self-centered,” he says. “I don't think it's malicious. Dealers at least have a flexible cost structure. Factories don't. It is, ‘Let's take care of our own problems first.’

“Now is the time to work together on a common goal of selling more cars. No one wants to wake up saying they want to sell fewer cars.”